The Silent Judgment: How "Algorithmic Bureaucracy" is Redefining Home Maintenance.

The Architecture of the Silent Judgment

In the contemporary digital economy, a profound and largely invisible transformation has fundamentally altered the mechanisms by which individuals are assessed, categorized, and permitted to participate in the essential functions of society. We have transitioned from an era of relational trust—where financial and social credibility were gauged through human interaction, local knowledge, and the nuanced understanding of a bank manager—to a regime of "Algorithmic Bureaucracy." This new administrative reality is not composed of paper files, rubber stamps, and human discretion, but rather of opaque binary code, predictive modelling, and vast, interconnected federated databases that operate almost entirely beyond the sight, understanding, and control of the average citizen. It is a system where the antagonist is no longer a specific prejudiced individual or a corrupt official, but a systemic, institutionalized "Blind Faith in the Black Box." This prevalent belief system posits that digital data—no matter how flawed, decontextualized, or misinterpreted by rigid logic—is inherently more truthful and reliable than human testimony. The result is a landscape where millions of individuals are subject to "Algorithmic Vetting" before a human eye ever reviews their application, creating a societal conflict described by sociologists as "The Burden of Mechanical Worthiness." Humans are increasingly forced to learn and perform the rigid, unforgiving language of machines—optimizing keywords for Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS), managing credit utilization ratios to the decimal, and curating digital footprints—simply to survive economically. We are, in essence, "glitching" our own lives to fit into databases that cannot process nuance, ambiguity, or the messy, non-linear reality of human existence.

The consequences of this seismic shift are far-reaching, structural, and often devastating for those caught in the gears of the machine. We are witnessing the rapid entrenchment of "Digital Redlining," a phenomenon where pervasive data surveillance is utilized not merely to target advertisements, but to manage, monitor, and punish. This exclusion goes far beyond the inconvenience of being rejected for a credit card; it manifests as being "de-banked," "de-hired," and erased from the economic map by systems that prioritize aggressive risk aversion over fairness or accuracy. The "Digital Poorhouse," a concept articulated by tech critics and sociologists, describes how these surveillance technologies are disproportionately deployed to police the working class and the vulnerable, automating the denial of essential services like welfare, housing, and employment based on predictive risk scores rather than actual behaviour. The profound tragedy of this system lies in its opacity; when the computer delivers a verdict of "no," there is often no manager to speak to, no appeal process that involves meaningful human reasoning, and no clear explanation of the "undisclosed reasons" for rejection. The individual is left fighting a ghost, arguing against a silent flag on a hidden database that has already rendered a verdict of "guilty until proven profitable" without a trial or the possibility of parole.

To fully comprehend the magnitude of this issue, one must look beneath the polished, user-facing interfaces of banking applications, tenant screening portals, and job application platforms to the subterranean infrastructure that powers them. This "Hidden" infrastructure consists of massive data consortiums like National Hunter, CIFAS, and SIRA—private entities that aggregate hundreds of millions of records regarding application data, fraud reports, and adverse media.1 These systems serve as the invisible gatekeepers of the modern economy. While their stated purpose is the prevention of fraud and financial crime—a necessary and legitimate goal in a complex financial system—their operational reality often resembles a dragnet that ensnares the innocent alongside the guilty with little distinction. A single "marker" or "flag" in one of these databases can metastasize across the entire financial ecosystem in milliseconds, leading to the immediate closure of bank accounts, the revocation of insurance policies, and a total blockade on future credit access. This is the "De-Banking" epidemic, a silent crisis where lawful individuals find themselves financially exiled without trial, jury, or effective remedy, often discovering the cause only after the damage is irreversible and their financial reputation has been shattered.

The philosophical and psychological underpinning of this automated system is "Automation Bias," a well-documented phenomenon where humans favour suggestions and decisions from automated decision-making systems and ignore contradictory information made without automation, even if the human information is correct. This bias leads bank staff, compliance officers, and even regulators to trust the "Fraud" marker on a screen over the protestations of a loyal customer standing in front of them, regardless of the evidence the customer presents. It is the precise logic that allowed the Post Office Horizon scandal to persist for decades: the unshakeable assumption that if the computer indicates a shortfall or a fraud, it must be true, and the human operator must be lying or incompetent. This report aims to rigorously deconstruct this "Algorithmic Bureaucracy," exposing the hidden mechanisms of exclusion, the lived reality of those labelled "risky" by machines, and the urgent need for "Data Dignity"—the moral and economic right to be seen as a human being, not merely a risk score or a data point in a syndicated list.

The Architecture of the Silent Judgment

In the contemporary digital economy, a profound and largely invisible transformation has fundamentally altered the mechanisms by which individuals are assessed, categorized, and permitted to participate in the essential functions of society. We have transitioned from an era of relational trust—where financial and social credibility were gauged through human interaction, local knowledge, and the nuanced understanding of a bank manager—to a regime of "Algorithmic Bureaucracy." This new administrative reality is not composed of paper files, rubber stamps, and human discretion, but rather of opaque binary code, predictive modelling, and vast, interconnected federated databases that operate almost entirely beyond the sight, understanding, and control of the average citizen. It is a system where the antagonist is no longer a specific prejudiced individual or a corrupt official, but a systemic, institutionalized "Blind Faith in the Black Box." This prevalent belief system posits that digital data—no matter how flawed, decontextualized, or misinterpreted by rigid logic—is inherently more truthful and reliable than human testimony. The result is a landscape where millions of individuals are subject to "Algorithmic Vetting" before a human eye ever reviews their application, creating a societal conflict described by sociologists as "The Burden of Mechanical Worthiness." Humans are increasingly forced to learn and perform the rigid, unforgiving language of machines—optimizing keywords for Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS), managing credit utilization ratios to the decimal, and curating digital footprints—simply to survive economically. We are, in essence, "glitching" our own lives to fit into databases that cannot process nuance, ambiguity, or the messy, non-linear reality of human existence.

The consequences of this seismic shift are far-reaching, structural, and often devastating for those caught in the gears of the machine. We are witnessing the rapid entrenchment of "Digital Redlining," a phenomenon where pervasive data surveillance is utilized not merely to target advertisements, but to manage, monitor, and punish. This exclusion goes far beyond the inconvenience of being rejected for a credit card; it manifests as being "de-banked," "de-hired," and erased from the economic map by systems that prioritize aggressive risk aversion over fairness or accuracy. The "Digital Poorhouse," a concept articulated by tech critics and sociologists, describes how these surveillance technologies are disproportionately deployed to police the working class and the vulnerable, automating the denial of essential services like welfare, housing, and employment based on predictive risk scores rather than actual behavior.1 The profound tragedy of this system lies in its opacity; when the computer delivers a verdict of "no," there is often no manager to speak to, no appeal process that involves meaningful human reasoning, and no clear explanation of the "undisclosed reasons" for rejection. The individual is left fighting a ghost, arguing against a silent flag on a hidden database that has already rendered a verdict of "guilty until proven profitable" without a trial or the possibility of parole.

To fully comprehend the magnitude of this issue, one must look beneath the polished, user-facing interfaces of banking applications, tenant screening portals, and job application platforms to the subterranean infrastructure that powers them. This "Hidden" infrastructure consists of massive data consortiums like National Hunter, CIFAS, and SIRA—private entities that aggregate hundreds of millions of records regarding application data, fraud reports, and adverse media.1 These systems serve as the invisible gatekeepers of the modern economy. While their stated purpose is the prevention of fraud and financial crime—a necessary and legitimate goal in a complex financial system—their operational reality often resembles a dragnet that ensnares the innocent alongside the guilty with little distinction. A single "marker" or "flag" in one of these databases can metastasize across the entire financial ecosystem in milliseconds, leading to the immediate closure of bank accounts, the revocation of insurance policies, and a total blockade on future credit access.8 This is the "De-Banking" epidemic, a silent crisis where lawful individuals find themselves financially exiled without trial, jury, or effective remedy, often discovering the cause only after the damage is irreversible and their financial reputation has been shattered.

The philosophical and psychological underpinning of this automated system is "Automation Bias," a well-documented phenomenon where humans favor suggestions and decisions from automated decision-making systems and ignore contradictory information made without automation, even if the human information is correct.1 This bias leads bank staff, compliance officers, and even regulators to trust the "Fraud" marker on a screen over the protestations of a loyal customer standing in front of them, regardless of the evidence the customer presents. It is the precise logic that allowed the Post Office Horizon scandal to persist for decades: the unshakeable assumption that if the computer indicates a shortfall or a fraud, it must be true, and the human operator must be lying or incompetent.1 This report aims to rigorously deconstruct this "Algorithmic Bureaucracy," exposing the hidden mechanisms of exclusion, the lived reality of those labelled "risky" by machines, and the urgent need for "Data Dignity"—the moral and economic right to be seen as a human being, not merely a risk score or a data point in a syndicated list.

Data indicates that algorithmic valuation models penalize visible exterior neglect as a primary indicator of deferred maintenance risk.

The Triad of Invisible Gatekeepers: National Hunter, CIFAS, and SIRA

The "Burden of Mechanical Worthiness" demands a shift in mindset. We must stop viewing Window Cleaning, Roof Cleaning, and Gutter Clearance as aesthetic choices. In 2026, these are "Asset Risk Management" protocols.

The Data Dignity of your Home: Just as you protect your credit score, you must protect your "Property Score." A Solar Panel Clean is not just about efficiency; it is proof that the system is maintained, preventing an automated "Risk Flag" on your insurance profile.

Predictive Home Resilience: By utilizing One Off Services like Soft Washing or Patio Cleaning, you are essentially "scrubbing" the negative data from your asset's physical profile.

The Human Verification: While the "Black Box" operates on assumptions, Shining Windows operates on Family Business values. We provide the "Right to Explanation" through our service logs. When we clean, we verify.

At the heart of the United Kingdom's financial vetting infrastructure sit three primary entities, often collectively referred to as the "Hidden Databases." It is crucial to distinguish these from the standard Credit Reference Agencies (CRAs) like Experian, Equifax, or TransUnion. While CRAs hold statutory credit files that are visible to consumers through statutory reports and apps like Credit Karma, the "Hidden Databases" are fraud prevention syndicates—private membership organizations where banks, insurers, and lenders share adverse data on "suspected" fraud and application inconsistencies. Accessing this data is difficult, correcting it is arduous, and the impact of a negative entry is catastrophic.

The first of these largely invisible gatekeepers is National Hunter. Operated by Experian Decision Analytics but functioning as a separate entity, National Hunter is often described as the "main database banks use to cross-check your application data." Its primary function is not to assess creditworthiness in the traditional sense (ability to pay), but to assess data consistency (honesty). When an individual applies for a credit card, loan, or mortgage, the details of that application—name, address, income, employment status—are fed into the National Hunter system. The system then compares this fresh data against millions of past applications filed by the same individual across different institutions over time.1 If a discrepancy is found—for example, a salary stated as £30,000 on a credit card application and £35,000 on a mortgage application three months later, or a different job title—the system flags this as an "inconsistency." While this logic is designed to catch "application fraud" (e.g., inflating income to secure a loan or hiding dependents), it lacks the nuance to distinguish between malicious intent, innocent error, or simply a legitimate change in circumstances.6 A freelance worker whose income fluctuates, or an applicant who made a typo in their employment duration, may find themselves flagged. This flag is frequently the cause of rejection for "undisclosed reasons," leaving the applicant bewildered and unable to correct a simple clerical mistake that has now been codified as a fraud risk across the entire banking sector.

The second, and perhaps most punitive, member of this triad is CIFAS (Credit Industry Fraud Avoidance System). While National Hunter focuses on application data consistency, CIFAS functions as the "National Fraud Database," recording instances where members believe there is "clear, relevant and rigorous" evidence of fraud.1 A CIFAS marker is not merely a warning; it operates as a digital scarlet letter or a "financial death sentence." The most common markers, such as "Misuse of Facility" (Category 6) or "First Party Fraud," act as a near-universal blacklist. Once a marker is placed, it remains for six years, during which time the subject is effectively exiled from the mainstream financial system.15 They may find their existing bank accounts closed, their mortgage applications denied, their car insurance cancelled, and even their mobile phone contracts revoked. Crucially, the evidentiary standard for placing a CIFAS marker is the civil standard ("balance of probabilities" or "reasonable grounds to suspect") rather than the criminal standard ("beyond reasonable doubt"). This means individuals can be branded as fraudsters and stripped of their financial access without ever being charged, let alone convicted, of a crime. This extra-judicial punishment is compounded by the fact that many victims of fraud—such as those whose identities have been stolen or young people who have been tricked into acting as "money mules"—find themselves registered on the database as perpetrators. The system struggles to differentiate between the criminal mastermind and the exploited victim, punishing both with equal severity.

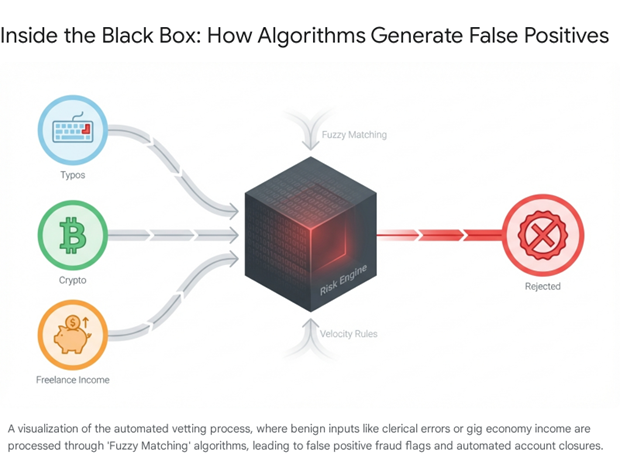

The third pillar of this surveillance triad is SIRA (Synectics Solutions), a syndicate database widely used in the insurance and finance sectors. SIRA aggregates a vast array of cross-sector data, including email addresses, phone numbers, device IDs, and IP addresses, to build complex risk profiles.7 Unlike the more binary nature of a credit score (pay or don't pay), SIRA and similar systems utilize probabilistic logic, including "fuzzy matching" and "velocity rules." Fuzzy matching identifies records that are similar but not identical—such as "Jon Smith" and "John Smith" at the same address—to link potentially disparate identities.19 Velocity rules flag unusual frequencies of activity, such as multiple credit applications or insurance quotes in a short window. While effective at spotting organized fraud rings that use synthetic identities, these algorithmic rules can easily generate false positives for legitimate consumers. A person shopping around for the best mortgage rate might trigger a velocity rule; a person with a common name might be erroneously linked to a fraudster via fuzzy matching.21 Once a "referral" is generated by SIRA, it creates a "consolidated view of risk" that is shared among all members. This means a flag raised by an innocent error on a car insurance quote can mysteriously result in a declined bank loan days later, with the consumer entirely unaware of the invisible thread connecting the two events.

These three systems—National Hunter, CIFAS, and SIRA—form an interlocking directorate of surveillance. They operate on the principle of reciprocity: members must share their own customer data to access the data of others. This creates a "network effect" where a suspicion held by one institution instantly becomes the "knowledge" of all. The danger lies in the lack of "Data Dignity" within this ecosystem. The data subject (the human) is treated not as a participant in this exchange but as a passive object of risk assessment. The systems are designed for the protection of the institutions, not the accuracy of the individual's record or their financial wellbeing. As a result, "error rates" in these databases—whether due to clerical mistakes, identity theft, or algorithmic misinterpretation—translate directly into life-altering harms for the individuals involved, who face a Kafkaesque struggle to clear their names against a bureaucracy that assumes the machine is always right.

The Architecture of the Silent Judgment

In the contemporary digital economy, a profound and largely invisible transformation has fundamentally altered the mechanisms by which individuals are assessed, categorized, and permitted to participate in the essential functions of society. We have transitioned from an era of relational trust—where financial and social credibility were gauged through human interaction, local knowledge, and the nuanced understanding of a bank manager—to a regime of "Algorithmic Bureaucracy." This new administrative reality is not composed of paper files, rubber stamps, and human discretion, but rather of opaque binary code, predictive modelling, and vast, interconnected federated databases that operate almost entirely beyond the sight, understanding, and control of the average citizen. It is a system where the antagonist is no longer a specific prejudiced individual or a corrupt official, but a systemic, institutionalized "Blind Faith in the Black Box." This prevalent belief system posits that digital data—no matter how flawed, decontextualized, or misinterpreted by rigid logic—is inherently more truthful and reliable than human testimony. The result is a landscape where millions of individuals are subject to "Algorithmic Vetting" before a human eye ever reviews their application, creating a societal conflict described by sociologists as "The Burden of Mechanical Worthiness." Humans are increasingly forced to learn and perform the rigid, unforgiving language of machines—optimizing keywords for Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS), managing credit utilization ratios to the decimal, and curating digital footprints—simply to survive economically. We are, in essence, "glitching" our own lives to fit into databases that cannot process nuance, ambiguity, or the messy, non-linear reality of human existence.

The consequences of this seismic shift are far-reaching, structural, and often devastating for those caught in the gears of the machine. We are witnessing the rapid entrenchment of "Digital Redlining," a phenomenon where pervasive data surveillance is utilized not merely to target advertisements, but to manage, monitor, and punish. This exclusion goes far beyond the inconvenience of being rejected for a credit card; it manifests as being "de-banked," "de-hired," and erased from the economic map by systems that prioritize aggressive risk aversion over fairness or accuracy. The "Digital Poorhouse," a concept articulated by tech critics and sociologists, describes how these surveillance technologies are disproportionately deployed to police the working class and the vulnerable, automating the denial of essential services like welfare, housing, and employment based on predictive risk scores rather than actual behaviour. The profound tragedy of this system lies in its opacity; when the computer delivers a verdict of "no," there is often no manager to speak to, no appeal process that involves meaningful human reasoning, and no clear explanation of the "undisclosed reasons" for rejection. The individual is left fighting a ghost, arguing against a silent flag on a hidden database that has already rendered a verdict of "guilty until proven profitable" without a trial or the possibility of parole.

To fully comprehend the magnitude of this issue, one must look beneath the polished, user-facing interfaces of banking applications, tenant screening portals, and job application platforms to the subterranean infrastructure that powers them. This "Hidden" infrastructure consists of massive data consortiums like National Hunter, CIFAS, and SIRA—private entities that aggregate hundreds of millions of records regarding application data, fraud reports, and adverse media.1 These systems serve as the invisible gatekeepers of the modern economy. While their stated purpose is the prevention of fraud and financial crime—a necessary and legitimate goal in a complex financial system—their operational reality often resembles a dragnet that ensnares the innocent alongside the guilty with little distinction. A single "marker" or "flag" in one of these databases can metastasize across the entire financial ecosystem in milliseconds, leading to the immediate closure of bank accounts, the revocation of insurance policies, and a total blockade on future credit access. This is the "De-Banking" epidemic, a silent crisis where lawful individuals find themselves financially exiled without trial, jury, or effective remedy, often discovering the cause only after the damage is irreversible and their financial reputation has been shattered.

The philosophical and psychological underpinning of this automated system is "Automation Bias," a well-documented phenomenon where humans favour suggestions and decisions from automated decision-making systems and ignore contradictory information made without automation, even if the human information is correct. This bias leads bank staff, compliance officers, and even regulators to trust the "Fraud" marker on a screen over the protestations of a loyal customer standing in front of them, regardless of the evidence the customer presents. It is the precise logic that allowed the Post Office Horizon scandal to persist for decades: the unshakeable assumption that if the computer indicates a shortfall or a fraud, it must be true, and the human operator must be lying or incompetent. This report aims to rigorously deconstruct this "Algorithmic Bureaucracy," exposing the hidden mechanisms of exclusion, the lived reality of those labelled "risky" by machines, and the urgent need for "Data Dignity"—the moral and economic right to be seen as a human being, not merely a risk score or a data point in a syndicated list.

Matthew Kenneth McDaid | The Architect

The Shining Windows Editorial Board

The "Data (Use and Access) Bill" highlights the rise of automated decision-making. Homeowners must now proactively manage their physical "data points" (cladding, fascia, driveways) to ensure favorable algorithmic treatment.

Boxed

Out

The Entrepreneurial

Balancing Act

The Mechanism of "Computer Says No": Fuzzy Logic and Black Box Vetting

The operational logic of the hidden databases is predicated on the concept of "Algorithmic Vetting," a process where Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning models decide the fate of an application before a human ever reviews it. This shift represents a fundamental change in the nature of bureaucracy. In traditional bureaucracy, rules were rigid but interpreted by humans who could exercise discretion based on context. In algorithmic bureaucracy, the rules are often opaque, dynamic, and executed by code that lacks the capacity for empathy, nuance, or contextual understanding.

The "Villain" here is not necessarily malice, but efficiency. Banks and large institutions process millions of applications; manual review is cost-prohibitive. Therefore, they rely on "Risk Engines" to filter the intake. These engines use complex algorithms to score applicants, and crucially, to identify "outliers." The problem is that the algorithm cannot distinguish between a "risky" outlier and a "unique" human situation. A legitimate change in address, a legal name change, or a complex income stream for a freelancer can all trigger the same "fraud" flags as a criminal syndicate.

A critical component of this mechanism is "Fuzzy Matching." Because data is rarely entered perfectly—typos happen, formats differ, names are abbreviated—databases use fuzzy logic to find probabilistic matches. While necessary for functionality, this introduces a significant margin for error. A strict algorithm might miss a match because of a single letter difference; a fuzzy algorithm might incorrectly link two innocent people because they share a date of birth and a similar name, or have lived at the same address at different times. When these "soft" matches are fed into a decision engine, they often harden into "hard" facts. The system sees a link to a fraudster (even a tenuous, incorrect one based on a fuzzy match score) and applies a high-risk score to the applicant. The "Automation Bias" of the human staff then kicks in: when the customer complains, the staff member sees the high-risk score on their screen and assumes the system has detected something they cannot see, rather than suspecting a system error or a data mismatch. The burden of proof shifts entirely to the individual to prove a negative—that they are not the person the computer thinks they are, or that the association is coincidental rather than conspiratorial.

The integration of AI into these systems is accelerating the opacity and the risk of unexplainable denials. As detailed in the uploaded documents, we are moving toward "Management by Algorithm" where the criteria for success or failure are dynamic and hidden. In the financial sector, the "black box" nature of modern machine learning models means that even the developers of the system may not be able to explain exactly why a specific applicant was rejected. The model might have identified a correlation between thousands of variables—spending patterns, device battery level, typing speed, email domain provider—that predicts a high probability of default or fraud.

This "inherent opacity" is the antithesis of due process. It creates a system where decisions are unchallengeable because they are unintelligible. The consumer asks "Why was I rejected?" and the institution can only answer "The model scored you too low." The parallel with the Post Office Horizon scandal is stark and terrifying: in that case, the courts and the institution believed a Fujitsu database over the testimony of honest humans for years, ruining thousands of lives. The lesson—"If it can happen to sub-postmasters, it can happen to your credit score"—is the central warning of the current era.

The "De-Banking" epidemic is the most visible and acute symptom of this mechanism. Recent years have seen a surge in account closures, with banks shutting down hundreds of thousands of accounts annually, often citing "financial crime concerns" or "risk appetite".

Behind these closures is often a silent trigger from a database like CIFAS or SIRA. A "Misuse of Facility" marker, perhaps triggered by a transaction the bank's AI deemed suspicious (such as a crypto purchase, a large transfer from family abroad, or usage patterns that deviate from the norm), can lead to an immediate exit. The "Computer Says Guilty" logic means that the bank does not need to prove the fraud in court; they only need to suspect it to a level that satisfies their own internal risk models. The customer receives a generic letter stating the relationship has broken down, with no specific reason given due to "tipping off" regulations (laws designed to prevent alerting money launderers, which are now routinely used as a shield against transparency for automated errors).

This leaves the individual in a state of helplessness, unable to challenge the evidence against them because they are not permitted to see it.

"We have transitioned from relational trust to... a systemic, institutionalized 'Blind Faith in the Black Box'." — The Invisible Verdict Research Paper (2026)

TRUSTED

DATA

The Antidote to the Black Box: Transparency

Digital Redlining and the "Digital Poorhouse"

The impact of these hidden databases is not distributed equally across the population. The concept of "Digital Redlining" suggests that the "mechanical worthiness" demanded by these systems effectively discriminates against those who live complex, non-standard lives—often the poor, the young, the self-employed, recent immigrants, and marginalized communities.1 The algorithms that power the hidden databases crave consistency: a steady salaried income, a fixed residential address for many years, a long and stable credit history. Those who deviate from this norm—gig workers with fluctuating income, students moving frequently between rentals, recent immigrants with thin credit files—are flagged as "high risk" anomalies or outliers. This is the "Digital Poorhouse," a modern surveillance state where the data of the working class is harvested and used to restrict their access to essential services rather than to empower them.

Statistics on financial exclusion paint a grim picture of this reality. In the UK, millions of adults are considered "credit invisible" or have "thin files," making them impossible to score using traditional methods. This forces them into the arms of high-cost subprime lenders or leaves them entirely unbanked.30 The rise of "automated rental rejection" extends this exclusion to housing, a fundamental human need. Landlords and letting agents increasingly use AI-powered tenant screening services that scour these same databases (National Hunter, CIFAS). A "false positive" on a fraud database, or even a low "tenant score" based on opaque criteria such as "lifestyle" data or spending habits, can lead to automatic rejection from housing, often without the applicant ever knowing why.31 This creates a class of "un-houseable" individuals who are locked out of the rental market not because of their actual behaviour (such as damaging property or not paying rent), but because of their data double. The "Ordinal Tenant" is born—a person defined solely by their rank in a digital sorting machine, stripped of their individual context.

The intersection of digital exclusion and the "hostile environment" for financial vetting creates a toxic, self-reinforcing cycle of despair. This mechanism operates as a "domino effect" of exclusion. It begins when an adverse marker is applied—perhaps a CIFAS marker for "Misuse of Facility" due to a misunderstood transaction. This triggers the first domino: the immediate closure of the individual's bank account. Without a bank account, the individual fails the credit check required for a new tenancy, leading to housing instability or homelessness. Simultaneously, the marker flags up during employment vetting, causing job offers to be withdrawn or leading to dismissal from roles in finance, law, or the civil service. The individual is thus trapped: unable to get paid, unable to rent a home, and unable to secure employment, all because of a single data point in a private database. This cycle transforms a financial dispute into a total social and economic lockout, creating a trap from which it is nearly impossible to escape without significant legal intervention.

For example, young people targeted as "money mules" often unknowingly allow their accounts to be used for transfers, attracted by "get rich quick" posts on social media or duped by "job offers" that turn out to be laundering schemes. When caught, they are hit with a CIFAS Category 6 marker ("Misuse of Facility"). This marker does not just close their current account; it effectively blacklists them from student loans, mobile phone contracts, and future employment in any sector requiring a background check. They are condemned to a "financial death" at the age of 18 or, often for a singular moment of naivety, with a punishment that lasts for six years—a disproportionate sentence handed down by a private database without a trial or the possibility of rehabilitation. Employers are increasingly checking "Enhanced Internal Fraud Databases" and other data pools to screen candidates. A marker intended to flag financial risk can thus become a barrier to earning a livelihood, trapping the individual in poverty and perpetuating the cycle of exclusion. This is the ultimate manifestation of the "Digital Poorhouse": a system where a data flag prevents you from getting a house, a job, or a bank account, effectively revoking your license to participate in the modern economy. The "data doppelganger"—the digital version of you stored in the cloud—has become more important than the physical you. If the doppelganger is flawed, the physical person suffers the consequences.

The Legal Void and the Fight for Data Dignity

The current legal framework is struggling to keep pace with the speed, scale, and opacity of Algorithmic Bureaucracy. The "Villain" is not just the technology itself but the "Blind Faith" placed in it by regulators, courts, and legislators.1 GDPR Article 22 theoretically gives individuals the right "not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing," which produces legal effects or similarly significant impacts. However, this protection is riddled with loopholes (e.g., the "necessity for contract" exemption) and is actively being weakened. The new Data Protection and Digital Information Bill in the UK aims to replace this "right" with more permissive provisions, potentially removing the requirement for human oversight in many cases in the name of innovation and efficiency.40 This creates a "Legal Void" where the automated decision is final, the logic is proprietary, and the human right to appeal is eroded to the point of non-existence.

Currently, if a person is "de-banked" or denied a mortgage due to a National Hunter or CIFAS marker, their path to redress is arduous, expensive, and slow. They must first realize what has happened—often after months of confusion. Then, they must file "Data Subject Access Requests" (DSARs) to multiple agencies (National Hunter, CIFAS, SIRA, the bank) just to find out which database holds the poison pill. Once the marker is identified, they must engage in a months-long battle with the institution that placed it. The institution often hides behind "commercial confidentiality" regarding their fraud detection rules or "tipping off" regulations to refuse any detailed explanation of why the marker was applied.43 The customer is left arguing against a secret accusation. If the bank refuses to remove the marker, the only recourse is the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), which is currently overwhelmed with backlogs stretching over a year.45 For a person who cannot pay rent because their bank account is frozen, or who cannot start a new job because they failed vetting, a year-long wait for justice is a denial of justice.

The solution, as proposed by digital rights advocates and forward-thinking ethicists, is "Re-humanising the Data Layer" and establishing Data Dignity.1 This concept, coined by Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl, argues that individuals should have moral and economic rights over their digital selves. It calls for an end to the "black box" society. We need "Algorithmic Accountability"—where decisions made by AI must be explainable to the human affected in plain language. If a mortgage is denied, the system should not just say "score too low," but explain specifically which data points caused the rejection (e.g., "The discrepancy between your income on the application and your tax return triggered the flag"). We need "Human-in-the-Loop" mandates that are meaningful, not tokenistic—a human who has the power, the training, and the authority to override the algorithm when it is visibly wrong, without fear of penalty.27

The fight for Data Dignity is the civil rights battle of the digital age. It is a demand that we be treated as more than the sum of our data points. It is a rejection of the "Digital Poorhouse" and a call for a system where technology serves human flourishing rather than administering automated punishment. Until we achieve this, we remain vulnerable to the "Silent Manager," the "Invisible Verdict," and the capricious whims of a code that cannot feel, cannot care, and cannot be reasoned with. The lesson of the Post Office Horizon scandal must be heeded: blind faith in the machine is a recipe for human tragedy. It is time to open the Black Box.

Evidence

Northamptonshire

Q &A Snippet: Q: How do I fight the "Invisible Verdict"?

A: With visible maintenance. Driveway Cleaning and Decking Cleaning remove the "decay signals" that algorithms flag.

Q: Is it complicated to book?

A: No. Unlike the banks, we are Mobile Friendly Online. You can Shop Online, see Prices Online, and get One Off Services instantly.

"From #Northampton to #MiltonKeynes, we see the same pattern. The well-maintained home is the resilient asset. We serve the #SurroundingVillages with the same precision as the town center."

Case Studies of Systemic Failure: The Evidence of Harm

To truly understand the human cost of Algorithmic Bureaucracy, we must examine the "Killer Case Studies" that serve as the "gold standards" of this crisis.1 These are not hypothetical scenarios but documented instances of systemic failure that reveal the brittleness of the current paradigm.

The Post Office Horizon Scandal stands as the ultimate historical proof of "Computer Says Guilty." For over a decade, hundreds of sub-postmasters were jailed, bankrupted, or driven to suicide because the courts and the Post Office blindy trusted the Horizon accounting database over the consistent testimony of honest citizens. The system showed money missing; therefore, the logic went, the humans must have stolen it. It took decades of legal battles to prove that the software was at fault—riddled with bugs, errors, and remote access vulnerabilities.2 This is not a historical anomaly to be dismissed; it is the blueprint for how modern algorithmic systems operate. The same "presumption of machine infallibility" is applied today when a bank's fraud detection system flags a customer. The bank assumes the algorithm has found a hidden truth that the customer is lying about. The Horizon scandal teaches us that when digital evidence contradicts human testimony, we must not default to believing the machine.

In the realm of personal finance, the logic of the "Uber Files" and the Gig Economy has infiltrated banking. Just as drivers are deactivated by bots for dipping below a rating threshold with no human appeal, bank customers are "de-banked" by algorithms for deviating from risk parameters. Stories from forums and consumer rights groups highlight the "De-Banking Epidemic." Consider the case of "Alienatrix1" 37, who raised a legitimate chargeback for a non-delivered item, only to have their credit card blocked and a CIFAS marker applied for "misuse of facility." The algorithm interpreted a consumer right (the chargeback) as a fraud risk (claiming money back illegitimately). Or consider "Canski" 38, whose identity was stolen to open fraudulent accounts. Despite proving their innocence and receiving compensation from the bank, the CIFAS "victim" marker (intended to protect them) resulted in a total blockade on opening new accounts four years later. Automated onboarding systems simply saw a "fraud" tag and rejected the application immediately, lacking the sophistication to distinguish between a "victim of fraud" and a "perpetrator of fraud."

These are not isolated incidents; they are systemic features of a high-volume, low-friction automated system. The "Error Rates" in these systems are not zero. Studies suggest significant percentages of credit reports contain material errors.1 In the context of fraud databases, a "false positive" rate of even 0.1% translates to thousands of innocent people being branded as financial criminals every year given the millions of accounts processed. The "De-Banking" of Nigel Farage brought political attention to the issue, but as the research shows, it happens to thousands of "normal people" via silent flags every day.8 Small business owners ("Junior_Winner1930") report having business accounts closed with "immediate effect and no reason given," followed by a domino effect of personal account closures, all traceable back to a single incorrect CIFAS marker.16 The human cost is immense: chronic stress, lost businesses, inability to pay staff, and the psychological toll of being treated like a criminal by a faceless system that refuses to engage.

The Legal Void and the Fight for Data Dignity

The current legal framework is struggling to keep pace with the speed, scale, and opacity of Algorithmic Bureaucracy. The "Villain" is not just the technology itself but the "Blind Faith" placed in it by regulators, courts, and legislators.1 GDPR Article 22 theoretically gives individuals the right "not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing," which produces legal effects or similarly significant impacts. However, this protection is riddled with loopholes (e.g., the "necessity for contract" exemption) and is actively being weakened. The new Data Protection and Digital Information Bill in the UK aims to replace this "right" with more permissive provisions, potentially removing the requirement for human oversight in many cases in the name of innovation and efficiency.40 This creates a "Legal Void" where the automated decision is final, the logic is proprietary, and the human right to appeal is eroded to the point of non-existence.

Currently, if a person is "de-banked" or denied a mortgage due to a National Hunter or CIFAS marker, their path to redress is arduous, expensive, and slow. They must first realize what has happened—often after months of confusion. Then, they must file "Data Subject Access Requests" (DSARs) to multiple agencies (National Hunter, CIFAS, SIRA, the bank) just to find out which database holds the poison pill. Once the marker is identified, they must engage in a months-long battle with the institution that placed it. The institution often hides behind "commercial confidentiality" regarding their fraud detection rules or "tipping off" regulations to refuse any detailed explanation of why the marker was applied.43 The customer is left arguing against a secret accusation. If the bank refuses to remove the marker, the only recourse is the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), which is currently overwhelmed with backlogs stretching over a year.45 For a person who cannot pay rent because their bank account is frozen, or who cannot start a new job because they failed vetting, a year-long wait for justice is a denial of justice.

The solution, as proposed by digital rights advocates and forward-thinking ethicists, is "Re-humanising the Data Layer" and establishing Data Dignity.1 This concept, coined by Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl, argues that individuals should have moral and economic rights over their digital selves. It calls for an end to the "black box" society. We need "Algorithmic Accountability"—where decisions made by AI must be explainable to the human affected in plain language. If a mortgage is denied, the system should not just say "score too low," but explain specifically which data points caused the rejection (e.g., "The discrepancy between your income on the application and your tax return triggered the flag"). We need "Human-in-the-Loop" mandates that are meaningful, not tokenistic—a human who has the power, the training, and the authority to override the algorithm when it is visibly wrong, without fear of penalty.

The fight for Data Dignity is the civil rights battle of the digital age. It is a demand that we be treated as more than the sum of our data points. It is a rejection of the "Digital Poorhouse" and a call for a system where technology serves human flourishing rather than administering automated punishment. Until we achieve this, we remain vulnerable to the "Silent Manager," the "Invisible Verdict," and the capricious whims of a code that cannot feel, cannot care, and cannot be reasoned with. The lesson of the Post Office Horizon scandal must be heeded: blind faith in the machine is a recipe for human tragedy. It is time to open the Black Box.

"Thank You for Your Time."

In an era often defined by speed and surface-level narratives, we recognize the value of the reader who seeks depth. Thank you for investing your time in this forensic analysis. We believe that clarity—whether in a pane of glass or a paragraph of text—is the only currency that matters. Your attention to detail mirrors our own, and for that, we offer our sincere gratitude.

If you wish to continue reading, the evidence room remains open.